By Molly Stech*

*The blog post below and the law review article it links to are the individual thoughts and views of the author and should not be attributed to any entity with which she is currently or has been affiliated.

In a forthcoming article in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, I review the law and jurisprudence concerning joint authorship and provide an analysis of it with specific emphasis on photographers and portrait subjects. I wrote and edited this paper in conjunction with the George Mason University Scalia School of Law’s 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship, and am very grateful for the thoughtful comments I received from Senior Commentators and scholars involved with the Fellowship.

In a forthcoming article in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, I review the law and jurisprudence concerning joint authorship and provide an analysis of it with specific emphasis on photographers and portrait subjects. I wrote and edited this paper in conjunction with the George Mason University Scalia School of Law’s 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship, and am very grateful for the thoughtful comments I received from Senior Commentators and scholars involved with the Fellowship.

A recent string of litigation in this space, and the general question of ownership interests in one’s own likeness, are what prompted my interest. Paparazzi have filed lawsuits against models and other celebrities for reposting images of themselves on their social media feeds, without permission from or compensation for the photographer. Some celebrities have countersued, but many of these cases settle out of court. In a best-case scenario, paparazzi and their subjects enjoy a mutually-beneficial relationship, but these lawsuits highlight a problematic legal space. It is accepted domestically and abroad that copyright subsists in the vast majority of photographs and that the copyright belongs to the photographer. The bar to copyrightability is notoriously low; it requires only a modicum of creativity.

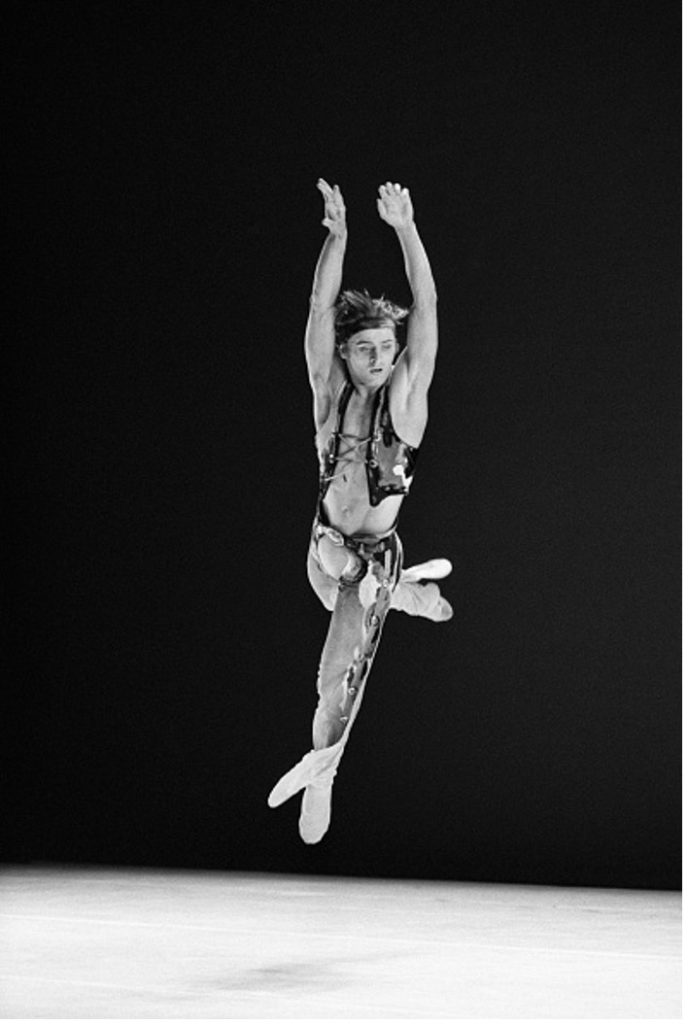

Photographers have a wide range of creative choices they can highlight to showcase where their authorship lies in a given photograph, including the camera and film used, the angle, the lighting, and the backdrop. What I explore in this paper is the possibility that subjects of photographs may also contribute copyrightable authorship to a given photograph, and may therefore be eligible to be deemed co-authors of certain photographs with the photographer. Copyright law aims to reward creative expression. Nothing in the statute can be read to proactively deny a subject co-authorship. I point out that copyright law is accustomed to doing the hard work of factual analysis (see, e.g., the fair use doctrine) and that any given work, including a photograph, should be considered on its own for purposes of correctly identifying authorial contribution. In some cases, a subject will contribute copyrightable expression by posing her limbs, arranging her facial expression, selecting her garments, or even arranging how her garments fall. So long as the contribution is adequately creative, co-authorship should be hers.

Joint (or Contributing) Authorship: Roadblocks

Two barriers to overcome in reaching this conclusion include some courts’ emphasis on joint authors’ intent; and some courts’ prerequisite that every contribution to a jointly-authored work be independently copyrightable. I address each of these problems in turn and underline that the statute itself does not make these requirements. Admittedly, in U.S. law, these are not easily surmountable obstacles. But, in taking copyright law back to its first principles, I believe the correct answer can be found in reemphasizing creative contribution. A recent case in the United Kingdom demonstrates an admirable flexibility that tailors an assignment of authorship to the degree of authorial contribution. An apportionment of authorship can be discerned from analyzing works one at a time. As mentioned, U.S. copyright law is no stranger to a work-by-work analysis in its fair use doctrine; another example is the idea-expression dichotomy, which provides that the more a work merges with its inevitable expression, the thinner its depth of copyright protection.

Other Thinking on These Issues

Any timely issue is likely to invite the contributions of other scholars, and this topic is no different. Other scholars have suggested sui generis rights for paparazzi subjects; separate types of exclusive rights for social media; and a personality-based right that could stretch copyright-like rights from covering “works” to people themselves. Another scholar argued persuasively for paparazzi subjects to receive an implied license to use photographs of themselves in certain ways. My analysis remains proscribed within copyright law itself, with the baseline argument that authorial creativity, whatever its guise, should be rewarded with rights.

There are other interesting avenues that are being explored to solve a similar problem, and I will follow them with interest. The right of privacy, a fascinating and complex legal discipline, may also offer solutions in the future. My paper mostly sidesteps the phenomenon of revenge porn, for example, and while a copyright argument could be made in the average scenario (no matter who pushes “record,” there are two people potentially offering creative expression to the final film), privacy law may be a more logical solution to protecting those subjects than copyright law. Another related argument that works in my favor, I believe, is rooted in freedom of expression. If copyright law is the engine of free expression, so should it contribute to people having a legal stake in their photographic likeness in order to control or at least contribute to the narrative attached to that photograph.

The paper is available in draft form at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4049946

And it will be available in late 2022 from Vanderbilt’s JETLaw website: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/

Santa Fe Saga, April 14, 1978. © Getty Images

Examples

While a revenge porn video may not make the best example for my analysis, I believe that selfies and photographs of dancers onstage do help demonstrate my view. A selfie is probably a copyrightable work. But in analyzing a given selfie to ascertain where the creativity lies, it will likely be in the pose, the facial expression, and the garments (the subject’s choices) as much as it will be in the framing, the backdrop, and the angle (the photographer’s choices). The photographer and the subject are of course the same person in the case of the selfie, but in deconstructing a photograph and searching for its authorial qualities, an argument certainly exists for the former forms of authorship as much as for the latter. And for a dancer onstage, his or her pose, facial expression, turnout, limb extension, jump arc, makeup, and any number of other attributes cannot reasonably be the result of the photographer’s efforts or talent, although the resulting photograph will of course likely benefit from them.

Conclusion

Co-authorship may exist in certain photographic portraits. It is essential that copyright law reexamine its interpretation of joint authorship in order to better capture and reward the contributions of the parties who offer creative expression to any given copyrightable work.