Last month, global health initiative UNITAID launched an appeal for suggestions on breaking down barriers that frustrate the progress of public health. UNITAID is a multilateral partnership hosted by the World Health Organization whose mission is to develop systematic approaches to identifying challenges in the treatment of devastating diseases such as HIV, TB, and malaria. The call for suggestions comes as UNITAID launches a renewed effort to improve access to health products for “the needy and vulnerable.”

Last month, global health initiative UNITAID launched an appeal for suggestions on breaking down barriers that frustrate the progress of public health. UNITAID is a multilateral partnership hosted by the World Health Organization whose mission is to develop systematic approaches to identifying challenges in the treatment of devastating diseases such as HIV, TB, and malaria. The call for suggestions comes as UNITAID launches a renewed effort to improve access to health products for “the needy and vulnerable.”

Unfortunately, UNITAID’s request takes a narrow view of the obstacles to a better public health system, choosing to blame intellectual property and patents for blocking access to life-saving medicines. The call for suggestions posits that while patents reward innovation, they also hamper access to drugs by limiting competition. After promoting several controversial mechanisms that would strip patent owners of their intellectual property rights, UNITAID urges responders to submit ideas that would further weaken patent systems around the world.

In response to UNITAID’s request, CPIP’s Mark Schultz and Kevin Madigan submitted comments that call attention to a serious and underappreciated problem detailed in the forthcoming white paper, The Long Wait for Innovation: The Global Patent Pendency Problem. Excessive patent application processing delays and inefficient patent systems are obstructing the distribution of ground-breaking new drugs by deterring both home-grown startups and foreign companies from investing in innovation. The following comments stress that effective property rights are critical to delivering health products to patients and that without a competent patent system, the market for medical innovations cannot function.

High-Level Suggestions to UNITAID on Intellectual Property Rights

Mark Schultz & Kevin Madigan[1]

September 15, 2016

We submit these comments in response to UNITAID’s call for high-level suggestions on intellectual property rights (IPRs). UNITAID’s request for suggestions observes that IPRs can pose a barrier to health products reaching “the needy and vulnerable.” However, the suggestions received will be incomplete if they fail to account for how effective IPRs are critical to delivering health products to patients.

An effective IPR system is essential to a well-functioning market in health products. It’s not just that patents secure investment in inventing a new cure; they also secure the investment made to bring that cure to patients in each market. A country’s ineffective IPR system can deter companies from making the substantial investments necessary to build a market in that country—these investments can include regulatory compliance, securing and negotiating reimbursement, building a distribution system, and educating health care providers about the benefits and administration of the drug. In fact, recent studies have shown a link between weak patent protection and delayed availability of drugs.[2]

In a forthcoming white paper for the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property at Antonin Scalia Law School, The Long Wait for Innovation: The Global Patent Pendency Problem, we illuminate an under-appreciated obstacle to bringing new drugs to patients. (The paper will be available soon at https://cip2.gmu.edu.) While debates and headlines focus on issues of patentable subject matter and exclusive property rights, the problem of patent pendency has been largely overlooked and under-examined. The reality is that in many countries, it simply takes too long to get a patent, thus deterring both home-grown startups and foreign companies from creating or even distributing ground-breaking new drugs.

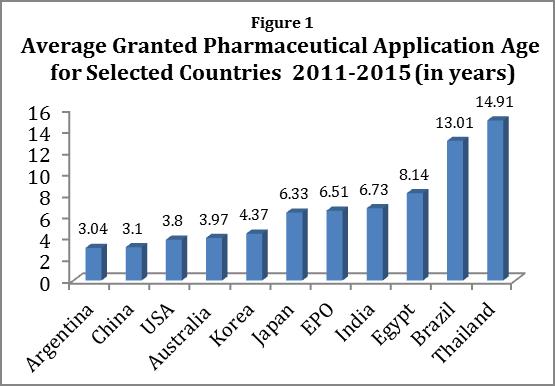

As Figure 1 shows, our study found that in 2011-2015, average time from application to grant for pharmaceutical patents ranged from Argentina, at 3.04 years, to Thailand at 14.91 years. The averages mask even worse problems—in 2015, Thailand issued 10 pharmaceutical patents with less than a year of term left. Five of them had 3 months or less of term left.

A long patent pendency period can deter a drug-maker from entering a market. Until a patent grant confirms that it can protect its investment in building a market, it is less likely to enter the market. If a company takes a wait-and-see approach, then consumers are in for a very long wait in countries such as Thailand and Brazil.

Causes of patent delay include a number of factors, many of which simply call for good governance. They include a simple lack of patent examiners and duplication of work already done by other capable patent offices. Our study suggests accelerated examination procedures, hiring more and better-qualified examiners, and work-sharing and recognition programs.

UNITAID is to be lauded for its innovative, market-based solutions, but well-functioning markets are founded on effective property rights. Without a competent patent system, the market for medical innovations cannot function. There should be a functioning market before one seeks to identify and correct market failures.

[1] Mark Schultz is Co-Founder and Senior Scholar at the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) at Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University. Kevin Madigan is Legal Fellow at CPIP. The views of the authors are their own and not those of CPIP or GMU.

[2] Iain M. Cockburn, Jean O. Lanjouw, & Mark Schankerman, Patents and the Global Diffusion of New Drugs, NBER Working Paper 20492, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20492 (2014); Ernst R. Berndt & Iain M. Cockburn, The Hidden Cost of Low Prices: Limited Access to New Drugs in India, 33 Health Affairs 1567 (2014); Joan-Ramon Borrell, Patents and the Faster Introduction of New Drugs in Developing Countries, 12 Applied Econ. Letters 379 (2005).