CPIP Founders Adam Mossoff & Mark Schultz filed an amicus brief today on behalf of 11 law professors in Converse v. International Trade Commission, a trademark case currently before the Federal Circuit.

CPIP Founders Adam Mossoff & Mark Schultz filed an amicus brief today on behalf of 11 law professors in Converse v. International Trade Commission, a trademark case currently before the Federal Circuit.

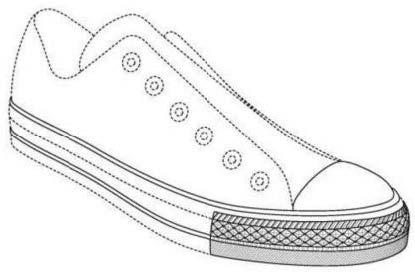

In late-2014, Converse filed a complaint with the International Trade Commission alleging that more than thirty companies, including Skechers, Walmart, New Balance, and Highline, were violating Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 by importing and selling infringing shoes. Converse owns a registered trademark on the midsole of its iconic Chuck Taylor All Star shoe, including the signature toe cap, toe bumper, and midsole stripes:

An administrative law judge found that Converse owns a valid registered trademark and that each respondent sold at least one infringing knock-off. That opinion was later reversed by the Commission, which held that Converse’s registered trademark was invalid. In the Commission’s opinion, Converse failed to prove that its iconic midsole had acquired secondary meaning—though it nevertheless found that Converse’s trademark would have been violated had it been valid. Converse has now appealed that ruling to the Federal Circuit.

The amicus brief filed by Professors Mossoff & Schultz argues that the Commission failed to properly consider the fundamental role of trademark law in securing the productive labors of companies like Converse that create famous products like its Chuck Taylor All Star shoe. The brief was co-signed by Professors Gregory Dolin, Christopher Frerking, Hugh Hansen, Jay Kesan, Irina D. Manta, Kristen Osenga, Eric Priest, Ted Sichelman, and Saurabh Vishnubhakat.

The Summary of Argument from the amicus brief is copied below:

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case deals with one of the most iconic, long-lived brands in the footwear industry: the Chuck Taylor athletic shoe. As one of the first massively successful athletic shoe products—selling hundreds of millions of pairs over the past 80 years—the name and design of these athletic shoes is an exemplar of the successful commercial goodwill that trademark law is intended to promote and secure to innovative commercial enterprises like Converse. Unfortunately, the International Trade Commission (Commission) chose to ignore the fundamental importance of investment in goodwill—to trademark law generally and to the establishment of secondary meaning specifically.

The appellant addresses the numerous doctrinal and factual infirmities with the Commission’s decision, and thus amici offer an additional legal and policy insight into this case that is necessary to understand the full scope of the Commission’s error: the Commission contradicted a fundamental precept of modern trademark law that it secures the valuable goodwill created by companies like Converse through their productive labors in creating, manufacturing and marketing iconic, famous products like the Chuck Taylor athletic shoes. See Qualitex v Jacobson, 514 U.S. 159, 163-64 (1995) (“The law thereby encourages the production of quality products, and simultaneously discourages those who hope to sell inferior products by capitalizing on a consumer’s inability quickly to evaluate the quality of an item offered for sale.”).

In addition to protecting consumers from significant costs and other harms imposed on them by commercial pirates, it is a longstanding, fundamental policy in trademark law to secure the valuable goodwill created by innovative commercial enterprises in selling products in the marketplace. See, e.g., Partridge v. Menck, 5 N.Y. Ch. Ann. 572, 574 (1847) (stating a trademark owner “is entitled to protection against any other person who attempts to pirate upon [its] goodwill”). Courts recognize these two key, mutually reinforcing policies in trademark law—securing goodwill and protecting consumers—as two sides of the same coin. See Groenveld Transport Efficiency v Lubecore Intern., Inc., 730 F.3d 494, 512 (6th Cir. 2013) (“Trademark law’s likelihood-of-confusion requirement . . . incentivizes manufacturers to create robust brand recognition by consistently offering good products and good services, which results in more consumer satisfaction. That is the virtuous cycle envisioned by trademark law, including its trade-dress branch.”). These two policies necessarily work together to ensure that trademark law functions properly.

In this case, the Commission disregarded the dual policies that animate trademark law by focusing solely on consumer issues while denying Converse its justly earned legal protection for its long-established and valuable goodwill. Thus, amici believe that the Commission’s decision should be reversed solely on the grounds of this contradiction of fundamental trademark policy. This is a case in which commercial pirates have undoubtedly “tread closely on the heels of [a] very successful trademark,” and thus are within the “long shadow which competitors must avoid” that is cast by Converse’s valuable goodwill in its famous mark—the Chuck Taylor athletic shoe design. Kenner Parker Toys Inc. v. Rose Art Industries, Inc., 963 F2d 350, 353-54 (Fed. Cir. 1992) (quotations and citations omitted).

To read the amicus brief, please click here.